Insulin Safety: Mastering Dosing Units, Syringes, and Preventing Hypoglycemia

Getting insulin dosing wrong isn’t just a mistake-it can land you in the hospital. One extra unit. One wrong syringe. One misread number. That’s all it takes for blood sugar to crash, and fast. In 2026, with all the technology we have, insulin errors still happen more often than they should. And the scariest part? Most of them are preventable.

Understanding Insulin Concentrations: U-100 vs. U-500

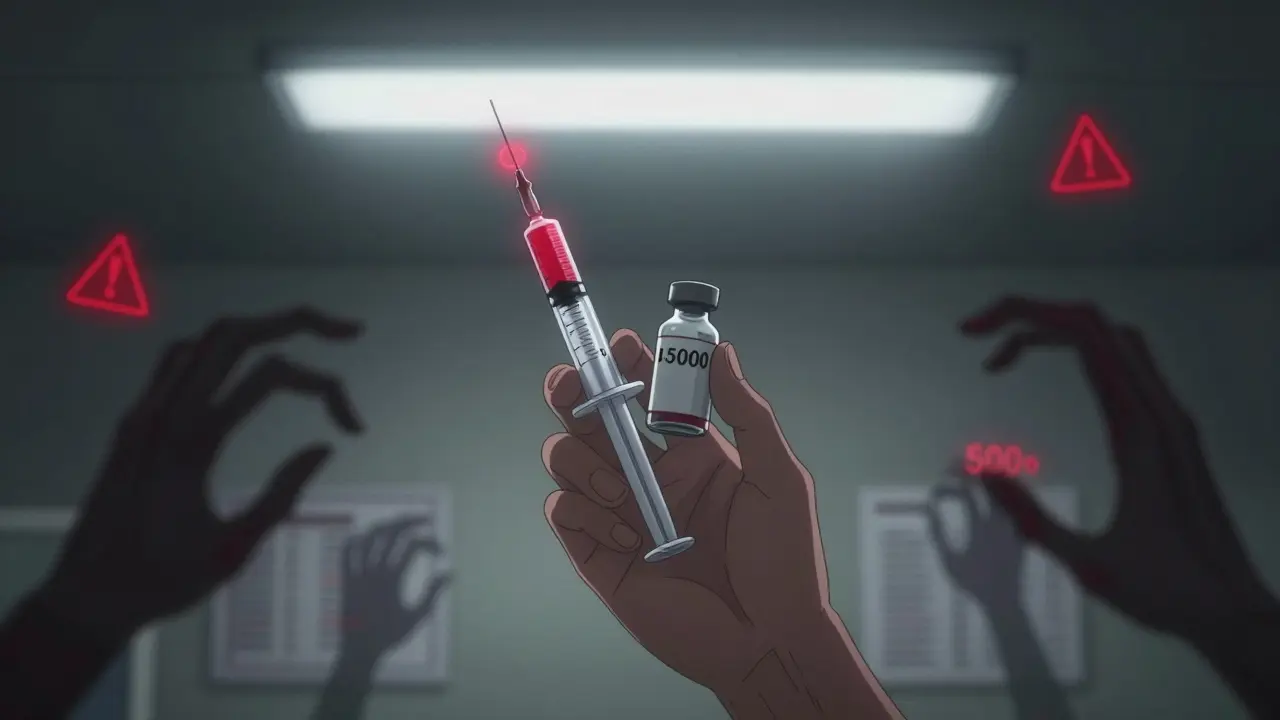

Not all insulin is the same. The most common type you’ll see is U-100 insulin. That means 100 units of insulin in every milliliter. It’s what most people use-whether they’re on rapid-acting insulin before meals or long-acting insulin at night. But there’s also U-500, which is five times stronger. That’s 500 units per mL. It’s usually prescribed for people with severe insulin resistance, like those with Type 2 diabetes who need huge doses.

Here’s the danger: if you use a U-100 syringe to draw up U-500 insulin, you’re giving yourself five times the dose you think you are. That’s not a typo. That’s a medical emergency. I’ve seen patients end up in the ER because they grabbed the wrong vial and thought they were giving 20 units-but they were actually giving 100. Always, always check the label. Write it on the vial if you have to. Never assume.

The Syringe That Could Kill You

Insulin syringes aren’t like regular ones. They’re marked in units, not milliliters. A U-100 syringe holds up to 100 units. A U-500 syringe is different-it’s usually labeled clearly, but people still mix them up. And here’s the real problem: some people use insulin pens, others use vials and syringes. If you’re switching between them, you need to know how to calculate the dose correctly.

Let’s say your doctor tells you to take 30 units of Lantus. You grab a U-100 syringe. You pull the plunger to the 30-unit mark. That’s correct. But if you’re using a U-500 vial and still using that same syringe? You’re giving yourself 150 units. That’s a 500% overdose. Hypoglycemia kicks in within minutes. Sweating. Shaking. Confusion. Then seizures. Then coma.

Always match your syringe to your insulin concentration. If you’re on U-500, you need a U-500 syringe. Period. There’s no shortcut. No guesswork. And if you’re ever unsure, ask your pharmacist to show you the right one. Don’t be embarrassed. This isn’t about being a good patient-it’s about staying alive.

The Hidden Math Behind Insulin Dosing

Insulin isn’t just about the number on the vial. It’s about math. And the math is often done wrong-even by professionals.

Here’s a big one: the conversion factor between insulin units and mass. Insulin is measured in units (U), not grams. But some lab reports and online calculators use the wrong number to convert between them. The correct factor is 5.18. But most tools use 6.0. That’s a 15% error. That means if your doctor says you need 40 units, and the system calculates it using the wrong factor, your actual dose might be off by 6 units. That’s enough to send your blood sugar crashing-or keep it dangerously high.

This isn’t theoretical. A 2018 study in PubMed found this error is everywhere-in journal articles, hospital software, even in some patient education materials. It’s not just patients getting it wrong. The system itself is broken. So always double-check your calculations. If you’re using an app or website to figure out your dose, ask your doctor if it uses the correct conversion factor.

How to Calculate Your Insulin Dose (The Real Way)

Most people think insulin dosing is simple: take X units before meals. But it’s not. It’s two parts: carbohydrate coverage and correction dose.

Let’s say you’re eating a meal with 60 grams of carbs. Your insulin-to-carb ratio is 1:12. That means 1 unit of insulin covers 12 grams of carbs. So 60 ÷ 12 = 5 units for your meal.

Now, your blood sugar is 220 before you eat. Your correction factor is 1 unit for every 45 mg/dL above target. Your target is 100. So 220 - 100 = 120. 120 ÷ 45 = 2.7 units. Round to 3 units.

Your total dose? 5 + 3 = 8 units.

That’s the formula. But here’s the catch: your ratio and correction factor are personal. They’re not the same as your neighbor’s. Your doctor figures them out using the Rule of 500 for carbs (500 ÷ total daily insulin = grams per unit) and the Rule of 1800 for corrections (1800 ÷ total daily insulin = mg/dL drop per unit). If you take 40 units a day, your carb ratio is 12.5 grams per unit. Your correction factor is 45 mg/dL per unit. That’s the math. Write it down. Keep it in your phone.

Basal Insulin: Starting and Adjusting Safely

If you’re starting long-acting insulin like Lantus, Basaglar, or Tresiba, your starting dose is usually 0.1 to 0.2 units per kilogram of body weight. For a 70 kg person, that’s 7 to 14 units. Many doctors start at 10 units-simple, safe, and easy to adjust.

Adjustments happen based on fasting blood sugar. If it’s above 180 mg/dL, add 8 units. Between 160-179? Add 6. 140-159? Add 4. If it’s below 60? Cut 4 or more units. Don’t guess. Don’t wait. Adjust every 2-4 days until your fasting number is in range.

And here’s something most people don’t know: if you switch from NPH to Lantus, you need to reduce your dose by 20%. So if you were on 60 units of NPH, you start with 48 units of Lantus. Going from Tresiba to Basaglar? Split your daily dose in half and give it twice a day. That’s not a suggestion. That’s the protocol. Mess this up, and you’re either under-dosed or over-dosed.

Hypoglycemia: The Silent Killer

Hypoglycemia doesn’t wait for you to be ready. It hits fast. And it doesn’t care if you’re a doctor, a nurse, or a 12-year-old. If your blood sugar drops below 70 mg/dL, you’re in danger.

Early signs: shaking, sweating, hunger, fast heartbeat. Later signs: confusion, slurred speech, weakness, seizures. If you’re alone and your blood sugar is below 60, you can’t always treat yourself. That’s why you need a glucagon kit-and someone who knows how to use it.

Glucagon isn’t just for emergencies. It’s your backup plan. Keep it in your bag. Keep it at work. Keep it with your kids. Know where it is. Practice using it. Glucagon kits are simpler now-no mixing needed. Just inject. It raises blood sugar in 10-15 minutes. If you’re not trained, ask your diabetes educator to show you. Do it now. Not tomorrow.

When Insulin Switches Go Wrong

Switching insulin types is common. Maybe your insurance changed. Maybe your doctor wants to try something newer. But each switch carries risk.

When moving from NPH to Lantus, you reduce the dose by 20%. From Lantus to Tresiba? You might need to lower it by 10-20% because Tresiba lasts longer and works more steadily. From rapid-acting Humalog to Fiasp? The timing changes. Fiasp acts faster, so you might need to inject closer to mealtime-or risk low blood sugar.

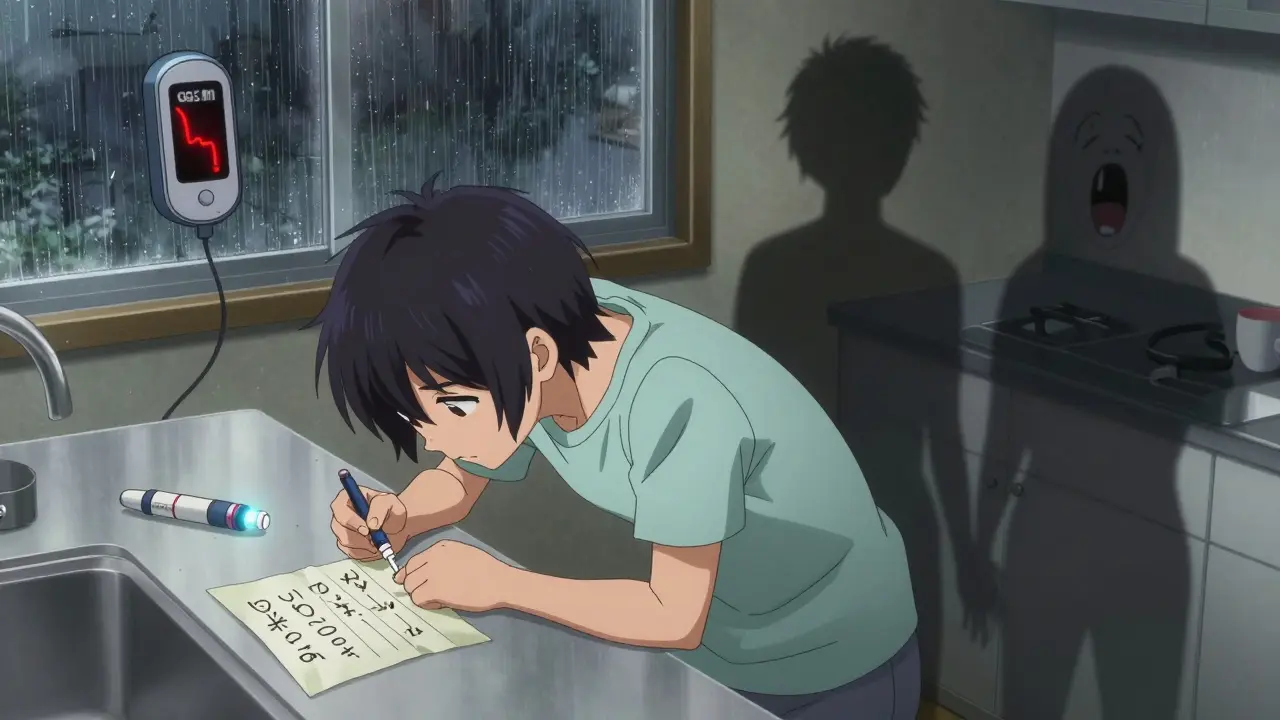

Always write down your old dose and your new dose. Compare them. Ask your pharmacist to explain the difference. And monitor your blood sugar more often for the first two weeks. Your body needs time to adjust. Don’t assume the dose stays the same. It rarely does.

Technology Can Help-But Not Replace Common Sense

Continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) are game-changers. They show trends, not just numbers. They warn you when your sugar is dropping. They’re especially helpful for people who don’t feel low blood sugar coming on-a condition called hypoglycemia unawareness.

But CGMs don’t fix bad math. They don’t stop you from grabbing the wrong syringe. They don’t replace knowing your insulin-to-carb ratio. Use them as a tool, not a crutch. Still check your blood sugar with a meter if you feel off. Still count carbs. Still calculate your dose.

And if you’re using an insulin pump? Make sure your settings are correct. A wrong carb ratio or correction factor in the pump can lead to repeated lows. Review your settings with your diabetes educator every 3 months.

Final Checklist: Your Insulin Safety Plan

- Always confirm insulin concentration (U-100 or U-500) on the vial before drawing up

- Use the correct syringe for your insulin type-never guess

- Know your insulin-to-carb ratio and correction factor-write them down

- Calculate your dose using both carb coverage and correction

- When switching insulins, reduce your dose as recommended by guidelines

- Keep glucagon on hand and know how to use it

- Check your blood sugar more often after any insulin change

- Ask your doctor or pharmacist to verify your dosing math

Insulin saves lives. But it can take them too-if you don’t treat it with the respect it deserves. The numbers don’t lie. The syringes don’t lie. Your body doesn’t lie. Get the math right. Get the tools right. And never, ever skip the safety steps.

Ian Cheung

Man I wish I had this post when I first started on insulin

I thought U-100 and U-500 were just different brands not different strengths

One time I grabbed the wrong vial at 2am and almost passed out

Now I label everything in neon sharpie and keep the syringes in separate drawers

Insulin doesn't forgive mistakes but it does reward caution

Michael Marchio

It's astonishing how many people treat insulin like it's ibuprofen

You don't just eyeball it, you don't swap syringes because 'they look similar', and you certainly don't rely on apps that use 6.0 instead of 5.18

The fact that this is even a discussion shows how dangerously complacent we've become

Every single hospital should have mandatory insulin safety training before discharge

And if your doctor doesn't explain the 500/1800 rule, find a new one

This isn't about being careful-it's about basic survival literacy

I've seen people lose limbs from one bad dose

And no, your 'I'm usually fine' attitude doesn't count

It only takes one time

Jake Kelly

This is such a clear and necessary guide

I appreciate how you broke down the math without making it feel overwhelming

I've been using a CGM for two years and it's been life-changing

But I still write down my ratios on a sticky note stuck to my fridge

And I always double-check the vial before I draw

Small habits save lives

Ashlee Montgomery

There's a quiet violence in how easily insulin can be misused

It's not malicious, just careless

And the system doesn't help-labels are too small, apps are outdated, pharmacists are rushed

We treat diabetes like a personal failure when it's really a systemic design flaw

Maybe the real issue isn't the patient forgetting their dose

But the world forgetting to make safety obvious

lisa Bajram

YESSSSS!!

I was just telling my cousin this last week-she switched from Humalog to Fiasp and didn't adjust timing and ended up in the ER

She thought 'it's just insulin' so the dose stays the same

NOPE

It's like swapping a sports car for a jet ski-same engine, totally different handling

Also-glucagon kits are not scary! They're like a fire extinguisher for your blood sugar

My 14-year-old daughter knows how to use mine

And she's not even diabetic

Everyone should have one

And yes, the 5.18 thing is a nightmare-I caught it in my diabetes app last month

Called my endo and they were like 'oh yeah, we updated that last year'

...why didn't I get an email?

Ritwik Bose

Respectfully, I would like to express my deep appreciation for the clarity and depth of this post.

As someone from India where access to proper diabetes education is uneven, this information is invaluable.

Many patients here rely on pharmacy advice, which is often inconsistent.

I have shared this with three community health workers in my village.

May I suggest that this be translated into Hindi and other regional languages?

It could save countless lives.

Thank you for your diligence.

Paul Bear

Let’s be precise: U-500 isn’t 'stronger'-it’s more concentrated. Terminology matters.

Also, the Rule of 500 is a heuristic, not a law. It assumes a fixed insulin sensitivity, which is rarely true in Type 2 with insulin resistance.

And you’re absolutely right about the 5.18 conversion factor-but it’s only valid for human insulin, not analogs like lispro or aspart.

Most literature still uses 6.0 because it’s easier to calculate, but that’s sloppy science.

Also, Tresiba to Basaglar? You don’t split the dose unless you’re transitioning from once-daily to twice-daily.

Basaglar is a biosimilar to Lantus, not Tresiba.

And if your CGM alarms are set too high, you’ll miss early lows.

Every single point here needs a footnote.

But overall? Good intent. Just needs peer review.

Jaqueline santos bau

OMG I JUST REALIZED I’VE BEEN USING THE WRONG SYRINGE FOR 3 YEARS

I’M SO SCARED

My mom used to say 'you’re gonna kill yourself with that stuff' and I thought she was being dramatic

But now I’m sitting here holding a U-100 syringe and a U-500 vial and I’m shaking

My doctor never told me

I just assumed they were the same

I’m calling my pharmacy right now

And I’m buying glucagon

And I’m telling everyone I know

Thank you for this

I’m not okay but I’m going to be

Kunal Majumder

Bro this saved my life

I was on 60 units of NPH and switched to Lantus and took the same dose

Woke up in the hospital with BG of 32

After that I started writing everything down

Now I have a notebook with my ratios, dates, and what insulin I’m on

And I show it to every new nurse

It’s not about being paranoid

It’s about being smart

Aurora Memo

I’m a nurse and I’ve seen this happen too many times

Patients aren’t careless-they’re overwhelmed

They’re juggling medications, appointments, work, kids

And insulin is just one more thing

The system should make safety automatic

Not rely on patients to be perfect

But until that changes

Keep writing posts like this

They matter