Ulcers and Stomach Cancer: Risks, Warning Signs & Prevention

Stomach Cancer Risk Assessment Tool

This tool helps you understand your potential risk of ulcer-related stomach cancer based on key medical factors. Remember: Most ulcers are harmless, but certain conditions increase risk. Results are for informational purposes only and don't replace professional medical advice.

Ever wonder if that lingering ulcer could turn into something far worse? The short answer is that most ulcers stay harmless, but certain conditions can push them toward gastric cancer. Understanding the connection helps you spot red flags early and take steps to protect yourself.

Key Takeaways

- Most peptic ulcers are benign, but chronic infection with Helicobacter pylori is the single biggest driver linking ulcers to stomach cancer.

- Long‑standing inflammation, atrophic gastritis, and intestinal metaplasia are the main pathways from ulcer to malignancy.

- Warning signs such as unexplained weight loss, persistent vomiting, or black stools warrant immediate medical review.

- Eradicating H. pylori, using proton‑pump inhibitors wisely, and adopting a low‑salt, high‑fruit diet sharply lower cancer risk.

- Regular endoscopic surveillance is essential for anyone with a history of chronic ulcers or precancerous stomach changes.

What Exactly Is a Peptic Ulcer?

A peptic ulcer is a sore that forms on the lining of the stomach (gastric ulcer) or the first part of the small intestine (duodenal ulcer). The lining gets eroded when digestive acids breach its protective mucus layer.

Most ulcers appear because of two culprits: infection with Helicobacter pylori (often simply called H. pylori) or regular use of non‑steroidal anti‑inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like ibuprofen.

How Do Ulcers Form?

When H. pylori colonises the stomach, it releases toxins that inflame the lining, weaken the mucus barrier, and trigger excess acid production. NSAIDs, on the other hand, block prostaglandins, chemicals that normally keep the stomach lining protected.

Both pathways lead to the same endpoint: a breach in the mucosal wall that manifests as a painful sore. For most people, this is a temporary irritation that heals with medication.

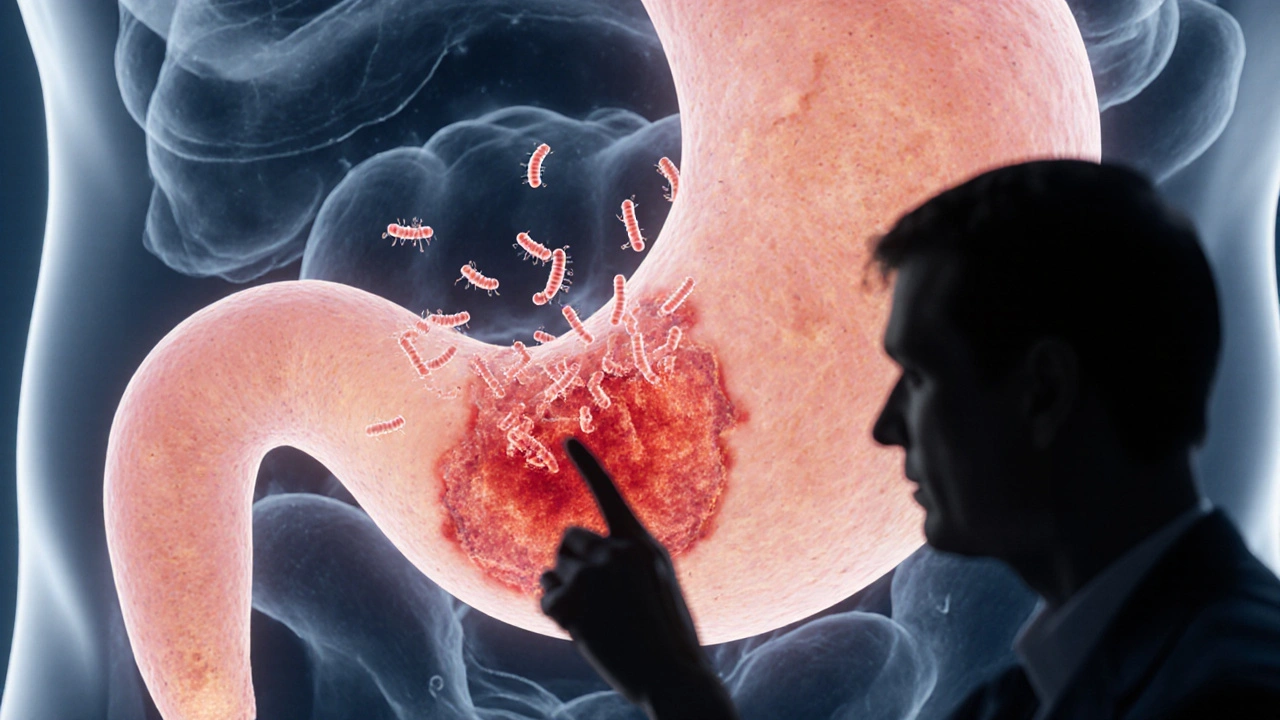

Is There a Direct Path from Ulcer to Cancer?

The link isn’t a straight line, but research from large epidemiological studies shows that people with chronic H. pylori‑induced ulcers have up to a 6‑fold higher risk of developing gastric cancer. The cancer type most often associated with ulcer disease is the intestinal type of gastric adenocarcinoma.

Why does this happen? Persistent inflammation sets off a cascade: normal stomach cells become damaged, gradually turning into atrophic gastritis, then into intestinal metaplasia, and finally into dysplasia - the exact steps that pave the way to cancer.

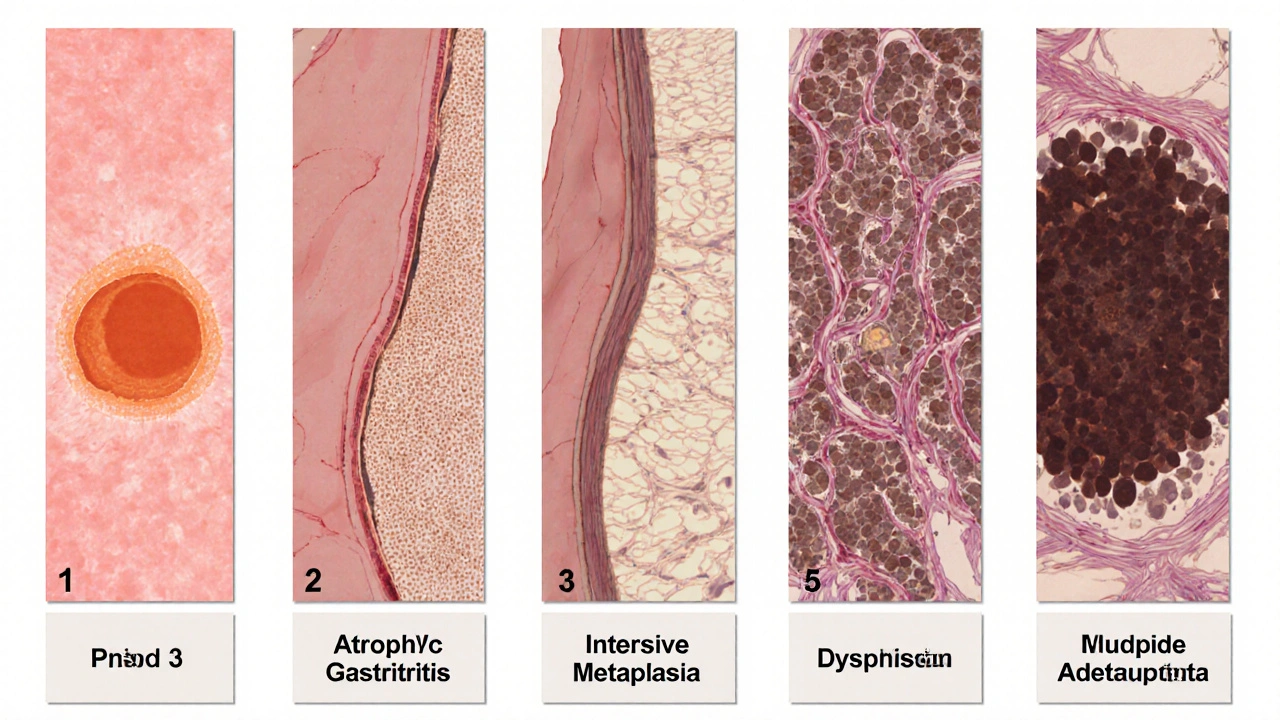

Key Biological Steps That Turn an Ulcer Into Cancer

| Stage | Typical Changes | Risk Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Chronic ulcer | Ongoing H. pylori infection, repeated acid damage | Creates a hostile environment for cells |

| Atrophic gastritis | Atrophic gastritis is a thinning of the stomach lining, loss of acid‑producing cells. | Reduces natural defenses, raises mutation risk |

| Intestinal metaplasia | Intestinal metaplasia replaces stomach cells with intestinal‑type cells. | These new cells are more prone to DNA errors |

| Dysplasia | Abnormal cell growth, precancerous lesions | High likelihood of progressing to carcinoma if left unchecked |

| Gastric cancer | Invasive tumor formation, possible spread | Clinical diagnosis often late; prognosis improves with early detection |

Warning Signs That Merit Immediate Attention

If you notice any of the following, it’s time to book an appointment right away:

- Unexplained weight loss of more than 5% of body weight over a few weeks.

- Dark, tar‑like stools (a sign of hidden bleeding).

- Persistent vomiting, especially if it contains blood.

- Severe, worsening abdominal pain that no longer eases after meals.

- Persistent fatigue or shortness of breath, indicating anemia.

These symptoms often overlap with benign ulcer flare‑ups, but when they appear together or last longer than two weeks, they become red flags for possible malignancy.

How Doctors Detect Cancer in Ulcer Patients

The gold standard is an upper endoscopy. A thin, flexible tube with a camera slides down the throat, letting the gastroenterologist inspect the stomach lining directly. If any suspicious area is seen, a biopsy is taken for lab analysis.

Histology can confirm atrophic changes, intestinal metaplasia, or early cancer cells. In high‑risk patients, doctors may schedule surveillance endoscopies every 1‑3years to catch malignant transformation while it’s still curable.

Prevention: Cutting the Risk Before It Grows

The most effective move is to eradicate H. pylori. A standard regimen-usually two antibiotics plus a proton‑pump inhibitor (PPI) for two weeks-clears the infection in over 90% of cases. After treatment, a follow‑up test ensures success.

Beyond antibiotics, lifestyle tweaks matter:

- Diet: Limit salty, smoked, and processed foods; load up on fresh fruits, vegetables, and legumes.

- Smoking: Quitting reduces cancer risk by about 30% within five years.

- Alcohol: Keep intake moderate (no more than one drink per day for women, two for men).

- NSAID use: Use the lowest effective dose, and consider protective PPIs if long‑term use is unavoidable.

These steps not only help heal existing ulcers but also halt the inflammatory cascade that fuels cancer.

When to Seek Medical Care

Even if you’ve never had an ulcer, any of the warning signs listed above deserve prompt evaluation. If you’ve been diagnosed with a chronic ulcer, schedule regular check‑ups, especially if you:

- Test positive for H. pylori and haven’t completed eradication therapy.

- Have a family history of gastric cancer.

- Experience repeated ulcer flare‑ups despite medication.

- Notice new symptoms like dysphagia (difficulty swallowing) or persistent nausea.

Early detection dramatically improves treatment outcomes; many early‑stage gastric cancers are cured with endoscopic resection alone.

Bottom Line

While most ulcers never become dangerous, chronic H. pylori infection, ongoing inflammation, and specific precancerous changes can transform a simple sore into ulcers and stomach cancer risk. By understanding the biological pathway, watching for warning signs, and following evidence‑based prevention, you can keep your stomach healthy and catch any trouble before it spreads.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can a healed ulcer still lead to stomach cancer?

If the ulcer healed without eradicating H. pylori or without addressing underlying atrophic changes, the risk remains. Continuous monitoring is advisable.

How long does it take for an ulcer to become cancerous?

The timeline varies; some studies suggest a decade of chronic inflammation before cancer develops, but the process can be quicker if multiple risk factors coexist.

Is endoscopy the only way to detect early gastric cancer?

Endoscopy with biopsy is the most reliable method. Imaging tests like CT scans are useful for staging but not for early detection.

Can a vegetarian diet lower my ulcer‑to‑cancer risk?

A plant‑rich diet reduces exposure to smoked and salted foods, both linked to higher cancer rates. It also offers antioxidants that may mitigate inflammation.

Do PPIs increase the chance of stomach cancer?

Long‑term PPI use has been associated with a modest rise in risk, likely because they can promote bacterial overgrowth. Use them under medical guidance, especially if you have H. pylori.

Nick Rogers

Excellent overview, the article succinctly outlines the key risk factors associated with peptic ulcers and gastric carcinoma; the inclusion of a risk assessment tool is particularly helpful, especially for individuals seeking to understand their personal risk profile.

Tesia Hardy

Ths is a verry informative post, i love how it breaks down the steps from ulcer to cancer. Great job, hope many read this and get checked early!

Ibrahim Lawan

Reading through this piece, one cannot help but appreciate the intricate cascade that transforms a seemingly benign ulcer into a malignant lesion. The narrative begins with the chronic presence of Helicobacter pylori, a bacterium that not only provokes inflammation but also manipulates the gastric environment to favor carcinogenesis. Persistent inflammation leads to atrophic gastritis, a condition where the protective mucosal layer thins and loses its functional capacity. This atrophy sets the stage for intestinal metaplasia, where gastric epithelium adopts an intestinal phenotype, rendering cells more susceptible to genetic errors. Over time, these metaplastic cells may progress to dysplasia, a precancerous state marked by abnormal cellular architecture. Dysplasia, if left unchecked, can evolve into overt gastric adenocarcinoma, a malignancy that often remains asymptomatic until advanced stages. It is noteworthy that the risk is amplified in individuals who simultaneously smoke, use NSAIDs, or possess a familial predisposition to gastric cancer. The article wisely emphasizes that eradication of H. pylori can interrupt this pathogenic sequence, underscoring the importance of timely antibiotic therapy. Moreover, lifestyle modifications-such as reducing salt intake, quitting smoking, and moderating alcohol consumption-serve as adjunctive measures to diminish oncogenic potential. Regular surveillance endoscopy for high‑risk patients allows for the detection of early mucosal changes before they become irreversible. In clinical practice, the integration of a structured risk assessment tool, as presented here, empowers both physicians and patients to make informed decisions regarding monitoring frequency and therapeutic interventions. Ultimately, the key takeaway is that while most ulcers remain innocuous, a small subset, under the right constellation of risk factors, can indeed serve as a gateway to gastric cancer; vigilance, therefore, is paramount. By fostering awareness and encouraging proactive management, we can substantially reduce the burden of gastric malignancies linked to chronic ulcer disease.

Leah Robinson

Wow, this is super helpful! 😊 I had no idea that H. pylori could be such a big deal. Definitely gonna schedule an endoscopy if I notice any of those warning signs. Thanks for the clear breakdown! 👍

Abhimanyu Lala

Great points, Ibrahim. Short and sweet: early eradication = lower risk.

Richard Sucgang

The article is thorough yet could benefit from a more nuanced discussion of the molecular pathways implicated in carcinogenesis, particularly the role of CagA-positive H. pylori strains which orchestrate oncogenic signaling cascades.

Justin Channell

👍 This summary is clear, thanks! 😃

Basu Dev

Building upon Abhimanyu's succinct observation, it is essential to recognize that the temporal dimension of ulcer chronicity is not merely a chronological fact but a biologically significant variable. Long‑standing mucosal injury provides a persistent inflammatory milieu, fostering DNA damage through reactive oxygen species. The cumulative effect of repeated cycles of injury and repair leads to clonal expansion of mutated cells, which may eventually escape normal regulatory mechanisms. In clinical practice, this underscores the necessity of periodic endoscopic surveillance for patients with ulcers persisting beyond one year, especially when accompanied by histologic evidence of atrophic changes. Moreover, the decision to initiate eradication therapy should be guided not only by symptom relief but also by the potential to halt the progression toward metaplasia. While the article outlines lifestyle interventions, a deeper exploration of dietary antioxidants, such as flavonoids found in berries and green tea, could further empower patients in risk reduction strategies. Finally, interdisciplinary collaboration among gastroenterologists, primary care physicians, and nutritionists is paramount to ensure a comprehensive approach that addresses both the microbial and host factors contributing to carcinogenesis.

Krysta Howard

Nice article, but I think it downplays the risk for people who constantly pop NSAIDs. 😠 You should stress that more!

Elizabeth Post

While the emphasis on H. pylori eradication is appropriate, the piece could also highlight the importance of monitoring for iron‑deficiency anemia as an indirect indicator of occult bleeding.

Brandon Phipps

Expanding on Basu's observations, let me add that the psychosocial impact of living with a chronic ulcer should not be overlooked. Patients often experience anxiety related to the fear of malignancy, which can affect adherence to treatment regimens. Incorporating mental health support, such as counseling or support groups, into the management plan may improve outcomes. Additionally, emerging research suggests that the gut microbiome beyond H. pylori plays a role in mucosal health; probiotic supplementation could be a valuable adjunct in restoring microbial balance after antibiotic therapy. Finally, clinicians should consider a personalized risk calculator-integrating age, sex, comorbidities, and genetic predispositions-to stratify patients more accurately for surveillance intervals. By adopting a holistic, patient‑centered approach, we can not only reduce the incidence of gastric cancer but also enhance overall quality of life for those affected by chronic ulcer disease.

yogesh Bhati

Yo, I think we should also talk about how stress can mess with your stomach lining. Many people ignore that, but it's real! Plus, dont forget to check for vitamin D levels; low levels can slow healing.

Akinde Tope Henry

Stress and vitamin D are minor compared to H. pylori prevalence in our community; focus should remain on eradication.

Brian Latham

Honestly, the article is fine but a bit overhyped. Most ulcers never become cancer.

Barbara Todd

I see your point, Brian, but ignoring the risk could be dangerous for those with multiple factors.

nica torres

Great discussion! 🌟 Remember, staying proactive with screenings and lifestyle changes is the best defense! Keep it up, everyone! 💪