Economic Impact of Patent Expiration: When Drug Prices Drop

When a drug’s patent expires, it doesn’t just change hands-it changes price. For patients, insurers, and pharmacies, this moment marks the start of a dramatic shift in how much they pay for medicine. What was once a costly brand-name drug can suddenly become a fraction of its original price, sometimes as low as $10 a month instead of $800. This isn’t magic. It’s economics. And it happens every single day across the U.S. and around the world.

How Patent Expiration Triggers Price Collapses

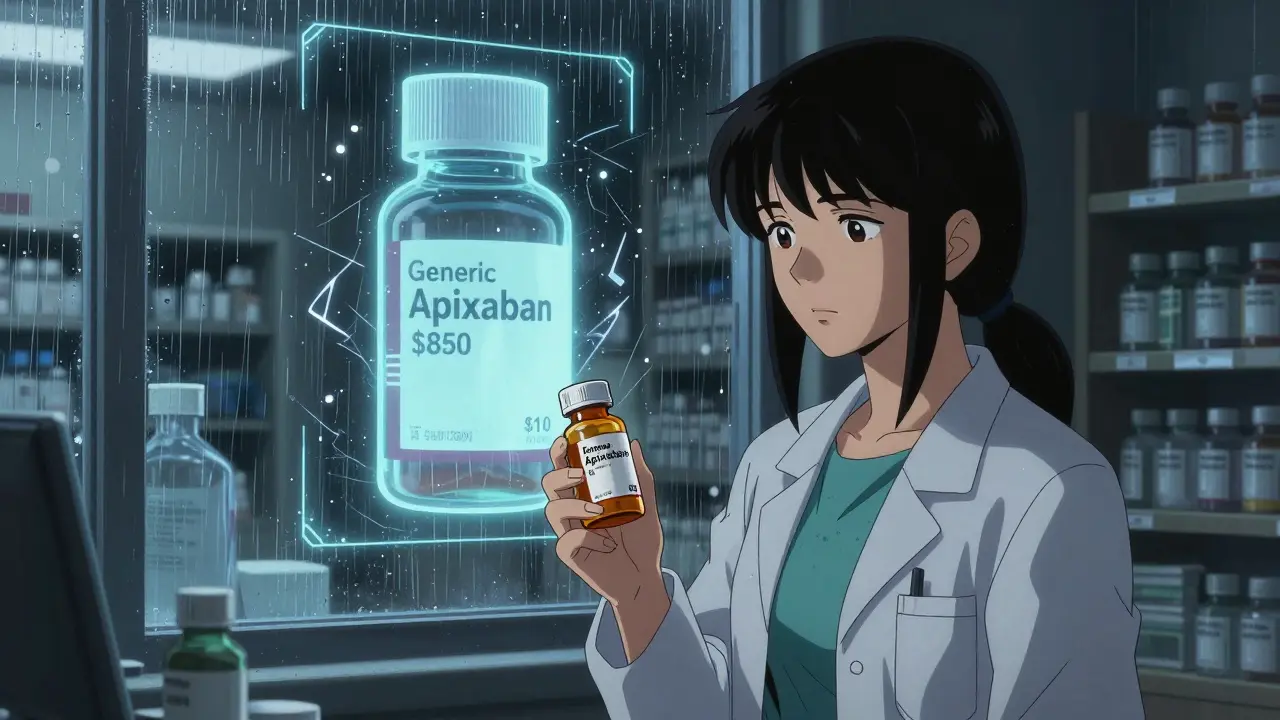

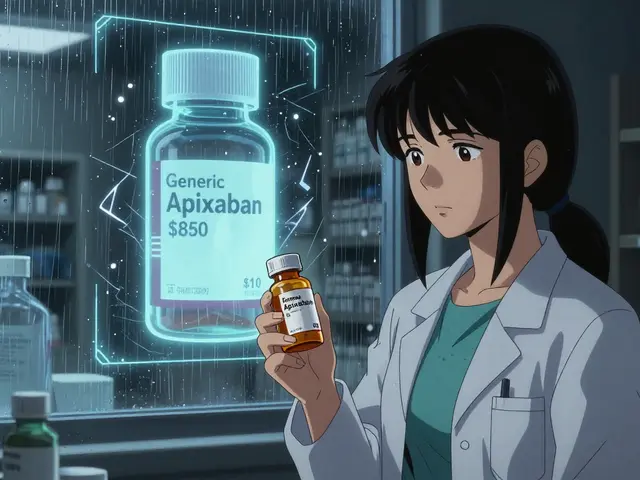

Patents give drugmakers exclusive rights to sell a medication for about 20 years. During that time, they’re the only ones allowed to make it. No competition. No pressure to lower prices. That’s why a drug like Eliquis (apixaban) could cost over $850 a month before its patent expired in 2020. Once the patent ran out, generic versions flooded the market. Within months, the same drug dropped to $10 a month. That’s a 98% price drop. The key isn’t just one generic company entering. It’s the domino effect. The first generic usually cuts prices by 15-20%. The second cuts them another 30-40%. By the time five or six companies are selling the same pill, prices often fall by 80-90%. The FDA tracks this closely. In 2023, it approved 870 generic drugs-12% more than the year before. Many of those were for high-cost medications just past their patent cliff.Why Some Drugs Don’t Drop in Price-Even After Patents Expire

Not all drugs follow this pattern. Some stay expensive long after patents expire. Take Humira (adalimumab). Its original patent expired in 2016, but prices didn’t fall until 2023. Why? Because the manufacturer, AbbVie, filed over 130 secondary patents-on tiny changes like packaging, dosing schedules, or injection devices. These weren’t new drugs. They were legal tricks to keep competitors out. This tactic, called “patent thickets,” is now common. A 2025 report from I-MAK found that 78% of new patents filed for existing drugs were not for real innovations but for ways to delay generics. Even when biosimilars (generic versions of biologic drugs) finally enter the market, prices don’t always drop right away. Why? Rebates. Insurance companies and pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) often get big discounts from the brand-name maker in exchange for keeping it on their preferred list. So even if a cheaper biosimilar is available, your insurance might not cover it. Patients end up paying full price for the original drug-because the system rewards secrecy, not savings.Country-by-Country Price Drops

The U.S. isn’t the only place where patent expiration matters. But it’s the most extreme. A 2023 study in JAMA Health Forum looked at eight wealthy countries. After eight years, drug prices fell:- 82% in the United States

- 60% in the UK

- 58% in Germany

- 53% in France

- 48% in Canada

- 42% in Japan

- 64% in Australia

- 18% in Switzerland

What Happens When Generics Finally Arrive

The FDA’s Generic Drug User Fee Amendments (GDUFA), started in 2012, were supposed to speed up approval. And they did-for simple pills. For a basic tablet, approval now takes about 10 months. But for complex drugs-like injectables, inhalers, or biologics-it can take over two years. Why? Because testing them is expensive. A single bioequivalence study can cost $2-5 million. Only big companies can afford that. That’s why some drugs stay expensive for years after patent expiration. Take semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy). The base patent expires in 2026. But the manufacturer has filed 142 patents on formulations, delivery methods, and dosing schedules. Experts predict these patents could delay true generic competition until 2036. That means millions of people with diabetes or obesity may keep paying $1,000+ a month for another decade.The Real Impact on Patients and Providers

For patients, the difference is life-changing. A 2023 Kaiser Family Foundation survey found 68% of insured adults saw lower out-of-pocket costs when generics launched. But 22% said their insurance didn’t switch to the cheaper version for months-or ever. Some pharmacists report patients showing up confused: “I got the same pill, but it’s still $700. Why?” Doctors see it too. Dr. Sarah Kim, a rheumatologist in Chicago, says patients with arthritis used to skip doses because they couldn’t afford Humira. Now, with biosimilars available, many are finally getting consistent treatment. But she still sees patients stuck on expensive brands because their insurer won’t cover the cheaper option.

What’s Changing-and What’s Not

There’s momentum for reform. The Inflation Reduction Act of 2023 lets Medicare negotiate prices for 10 high-cost drugs a year. That’s forcing manufacturers to rethink their strategies. Some are rushing to launch generics before their drugs get picked for negotiation. Others are filing even more patents to stretch out exclusivity. The European Union is moving faster. Its 2024 Pharmaceutical Package limits how long companies can extend patents with minor changes. The European Medicines Agency wants 70% of patients on biosimilars within three years of patent expiry-up from 45% today. In the U.S., the Patent Trial and Appeal Board started cracking down on patent thickets in 2023. But progress is slow. Until there’s real transparency in rebate deals and faster approval for complex generics, many patients will keep paying far more than they should.What You Can Do

If you’re on a drug that just lost its patent:- Ask your pharmacist: “Is there a generic version?”

- Ask your doctor: “Can we switch to a biosimilar or generic?”

- Call your insurer: “Why isn’t the cheaper version covered?”

- Check GoodRx or NeedyMeds: They often list prices for generics before insurers update their lists.

Do all drugs drop in price after patent expiration?

Not always. Simple pills usually drop 80-90% within a few years. But complex drugs-like injectables, inhalers, and biologics-can stay expensive for years due to high approval costs, patent thickets, and insurance rebate deals. Drugs like Humira and Ozempic are examples where prices didn’t fall immediately after patent expiry.

How long does it take for generics to appear after a patent expires?

In the U.S., generics typically enter 12-30 months after patent expiry, depending on legal challenges. In Europe, it’s often 12-18 months. For complex drugs, approval can take over two years. Some companies delay entry through lawsuits or patent extensions.

Why are some generic drugs still expensive?

Even if a generic is available, your insurance may not cover it. Manufacturers often pay rebates to keep their brand on preferred lists. Also, some generics are made by only one company, so there’s no competition to drive prices down. Supply chain issues and manufacturing delays can also limit availability.

What’s the difference between a generic and a biosimilar?

Generics are exact copies of small-molecule drugs (like pills). Biosimilars are similar-but not identical-to complex biologic drugs (like injectables made from living cells). Because biologics are harder to copy, biosimilars require more testing. They’re cheaper than the original, but not always as cheap as a typical generic.

Can I ask my doctor to switch me to a generic?

Yes. In fact, you should. Ask if a generic or biosimilar is available and if it’s covered by your insurance. Most states allow pharmacists to substitute generics unless your doctor writes “dispense as written.” But you need to initiate the conversation-many providers assume patients know about generics.

Jack Havard

Patent expiration doesn't fix anything. It just moves the problem from one corner of the system to another. The real issue is that we treat medicine like a commodity instead of a right. Companies don't stop gaming the system just because a patent expires. They just find new loopholes. And we keep acting surprised when the same drugs stay expensive. It's not broken. It's designed this way.

Gloria Ricky

i just switched my mom to the generic for her blood pressure med last month and she’s been saving $200 a month. she didn’t even know she could ask for it. pharmacists don’t always bring it up either. i’m so glad we found out through goodrx. it’s crazy how much we overpay when no one tells us there’s a cheaper option.

Stacie Willhite

I’ve been on a biologic for autoimmune disease for 8 years. When the biosimilar finally came out, my insurance didn’t cover it for 6 months. I had to pay full price on the brand-name while waiting. My out-of-pocket was $1,200 a month. Now it’s $45. But I almost gave up before it happened. If you’re struggling, don’t assume your provider knows what’s available. Ask. Keep asking. It’s exhausting, but it works.

Jason Pascoe

The Australia data is interesting. We’ve got a national pricing system, so when generics hit, they get slapped with a ceiling price. No haggling. No rebates. Just lower cost, straight to the consumer. It’s not perfect, but it’s way more predictable than the U.S. mess. I’ve seen people in the States pay 10x more for the same pill. It’s not about innovation. It’s about who gets to set the rules.

Rob Turner

The UK and Germany are doing better because they treat pharma like a public service, not a casino. Here in the UK, the NHS negotiates bulk prices. No one’s making 98% profit margins on a pill that costs 20 cents to make. I remember when my dad needed insulin - he paid £12 a month. In the US? $300. That’s not economics. That’s exploitation dressed up as capitalism.

Luke Trouten

There’s a deeper philosophical question here: if a drug saves lives, should it ever be subject to market forces? The patent system was meant to incentivize innovation, not create artificial scarcity. But we’ve turned it into a financial instrument. Companies don’t innovate to help people - they innovate to extend monopolies. And the system rewards that. We’re not just arguing about prices. We’re arguing about what kind of society we want to live in.

Gabriella Adams

The Inflation Reduction Act’s negotiation provision is a start - but 10 drugs a year? That’s less than 1% of high-cost medications. We need structural reform, not piecemeal fixes. And the rebate system must be eliminated. It’s a hidden tax on patients. If a biosimilar is approved and cheaper, it should be the default. Period. Insurance companies shouldn’t be allowed to profit from keeping people on expensive brands. Transparency isn’t optional - it’s ethical.

Kristin Jarecki

The FDA’s approval timelines for complex generics are a major bottleneck. A $5 million bioequivalence study is not a barrier to entry - it’s a wall. And only corporations with deep pockets can climb it. That’s why we see monopolies persist even after patents expire. We need public funding for generic testing infrastructure. Not more regulation. Not more lawsuits. Just investment in the science that makes affordable drugs possible.