How Medicare Drug Price Negotiations Work and What It Means for Your Costs

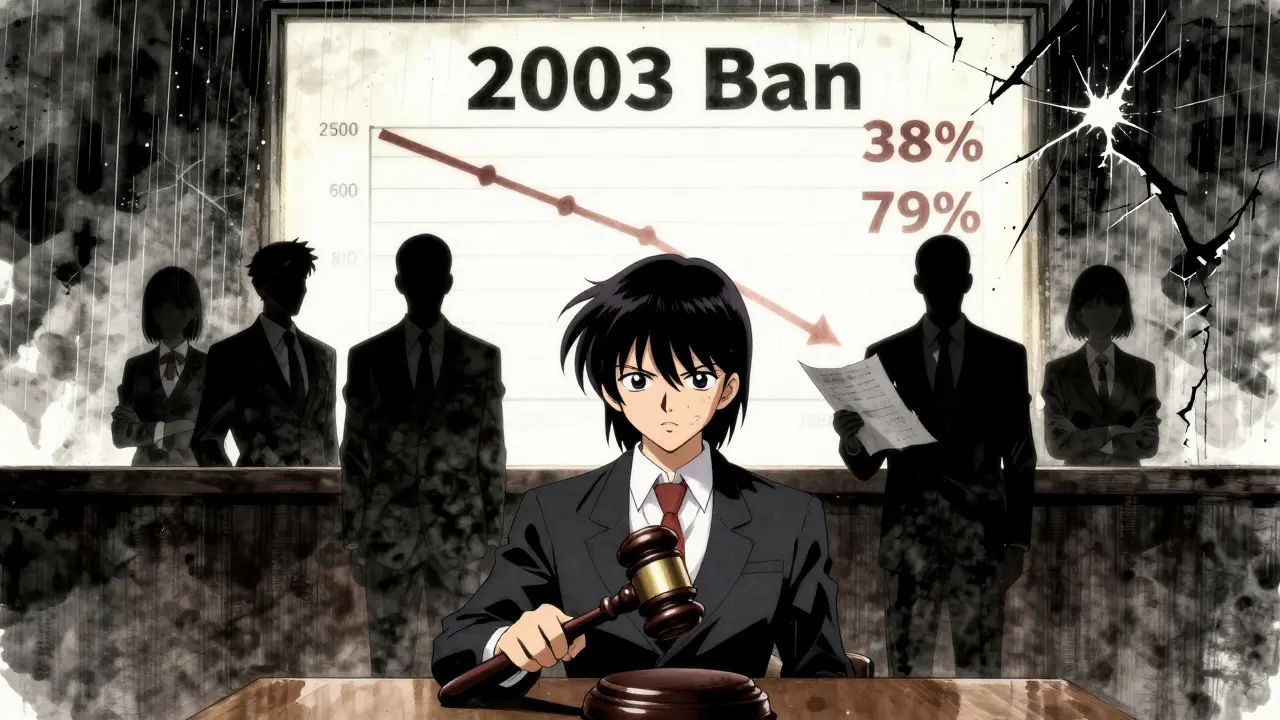

Starting January 1, 2026, millions of Medicare beneficiaries will see lower prices for 10 of the most expensive prescription drugs - not because of a sale, but because the federal government finally has the legal power to negotiate drug prices directly with manufacturers. This isn’t a new idea in other countries, but in the U.S., it’s a major shift. For decades, Medicare was banned from negotiating prices for Part D drugs, leaving billions in spending up to pharmaceutical companies to set. Now, that’s changing - and the discounts are substantial.

What Changed With the Inflation Reduction Act?

Before August 2022, Medicare couldn’t bargain for lower drug prices, even though it paid out $149.8 billion on prescriptions in 2021 alone. Private insurers could negotiate rebates, but Medicare had to pay whatever the manufacturer listed - often hundreds of dollars per pill. The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) broke that rule. For the first time, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) can step in and set a "Maximum Fair Price" for high-cost, single-source drugs with no generic or biosimilar competition. The law targets drugs that have been on the market for at least 7 years (or 11 for biologics). That means newer, cutting-edge drugs are off-limits for now, but older, high-revenue drugs like Eliquis, Jardiance, and Xarelto are fair game. These 10 drugs made up $50.5 billion in Medicare spending in 2022. Now, after months of negotiation, CMS has locked in discounts ranging from 38% to 79% off previous prices.How the Negotiation Process Actually Works

It’s not a back-and-forth haggle at a car dealership. It’s a strict, rule-bound process with deadlines and data requirements. Here’s how it unfolded for the first 10 drugs:- February 1, 2024: CMS sent each drugmaker an initial price offer - based on what other countries pay, what Medicare spent in the past, and how much cheaper alternatives are.

- March 2, 2024: Manufacturers had 30 days to respond with a counteroffer. Most lowered their prices, but few met CMS’s initial offer.

- Spring-Summer 2024: CMS held exactly three in-person or virtual meetings with each company. They didn’t just talk - they presented clinical data, usage stats, and cost comparisons.

- August 1, 2024: The deadline. Five drugs agreed during meetings. The other five settled through final written offers.

What Discounts Are You Seeing in 2026?

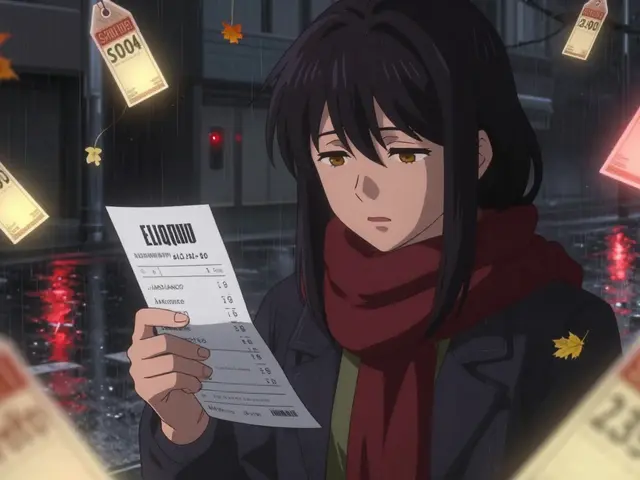

The results are clear. For example:- Eliquis (apixaban): Down 65% - from $550 to around $195 per month.

- Jardiance (empagliflozin): Down 79% - from $620 to $130.

- Xarelto (rivaroxaban): Down 58% - from $480 to $200.

Why This Matters for Private Insurers Too

You might think this only affects Medicare. But it doesn’t stop there. Private insurers often use Medicare’s prices as a benchmark. When CMS sets a new "fair price," companies like UnitedHealthcare, Humana, and Blue Cross start adjusting their own contracts. That’s called the "spillover effect." A 2024 analysis by the Pharmaceutical Care Management Association estimated that private insurers could save $200-250 billion over the next decade because of these negotiated prices. That means lower premiums, smaller copays, and fewer surprise bills for people with employer insurance - even if they’re not on Medicare.What About Doctors and Part B Drugs?

The same system is coming to Part B drugs - the ones you get in a doctor’s office or hospital, like cancer infusions or injections. Starting in 2028, CMS will begin negotiating prices for 15 more drugs in this category. But here’s the twist: doctors are paid based on the drug’s price. Right now, they get Average Sales Price (ASP) + 6%. In 2028, they’ll get the new Maximum Fair Price + 6%. That sounds fine - until you realize that if the drug price drops 50%, so does the doctor’s reimbursement. The American Medical Association estimates this could cut physician revenue by $1.2 billion in the first year alone. Some clinics might stop stocking these drugs, or shift patients to alternatives. That’s why the transition needs careful planning - and why CMS is releasing detailed guidance to help providers adapt.

Who’s Opposing This - and Why?

The drug industry isn’t happy. Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA) warned that the program could cut innovation funding by $112 billion over 10 years. They argue that lower prices mean less money for research. But the Office of Management and Budget called those estimates "significantly overstated." Four of the 10 drugmakers sued to block the program, claiming it was unconstitutional. In August 2024, a federal judge dismissed all four lawsuits. Appeals are expected, but for now, the law stands. Meanwhile, the FTC has stepped up enforcement against "product hopping" - when companies slightly tweak a drug just to delay generics. That’s helping clear the path for more drugs to become eligible for negotiation in the future.What This Means for You

If you’re on Medicare and take one of the 10 negotiated drugs, you’ll see lower prices starting January 1, 2026. You don’t need to do anything. Your plan will update automatically. If you’re not on Medicare but have private insurance, you may still benefit - through lower premiums or smaller copays as insurers adjust their pricing. If you’re worried about access: the law doesn’t force you to switch drugs. You can still get your current medication - just at a lower price. If your doctor prescribes a drug that’s now cheaper, you might even be able to ask for a generic alternative if one exists.What’s Next?

The program is just getting started. In 2027, 15 more drugs will be added. In 2028, Part B drugs enter the mix. By 2030, up to 20 drugs per year could be negotiated. The goal isn’t to punish drugmakers - it’s to make sure taxpayers and patients aren’t overpaying for medications that have been on the market for years. The big question isn’t whether this works - it’s how far it goes. Will Congress lower the 7-year eligibility rule? Will more drugs become eligible as generics arrive? Will other insurers follow Medicare’s lead? One thing is certain: the days of unchecked drug pricing in the U.S. are ending.Will my Medicare drug prices go down in 2026?

Yes - if you take one of the 10 drugs selected for negotiation. Prices for Eliquis, Jardiance, Xarelto, and seven others will drop by 38% to 79% starting January 1, 2026. Your plan will update automatically. You don’t need to take action.

Do these price cuts apply to people with private insurance?

Not directly, but likely yes. Private insurers often use Medicare’s negotiated prices as a benchmark. Many are already adjusting their contracts, which could lead to lower premiums, smaller copays, and fewer surprise bills for people with employer-based or individual plans.

Why did it take so long for Medicare to negotiate drug prices?

For over 20 years, a legal restriction banned Medicare from negotiating. That rule was written into the Medicare Part D law in 2003, under pressure from drug companies. The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 removed that ban after decades of public pressure and rising drug costs.

Can I still get my current medication if it’s on the negotiation list?

Absolutely. The price cut doesn’t mean your drug is being pulled from the market or replaced. You’ll still get the same medication - just at a much lower cost. Your doctor can still prescribe it, and your pharmacy will fill it as usual.

What if I’m not on Medicare? Will I still benefit?

You might. Private insurers often use Medicare’s negotiated prices as a reference point. As a result, many are lowering their own prices for the same drugs. This could lead to lower premiums, reduced copays, and better coverage for people with employer-sponsored or individual insurance plans.

Are there any risks to this program?

Some doctors worry they’ll earn less on Part B drugs, which could affect availability. Drugmakers claim it will hurt innovation - but government analysts say those fears are exaggerated. So far, the program has stayed within legal boundaries, and patient access hasn’t been disrupted. The biggest risk is political: if future administrations weaken the law, progress could stall.

Peyton Feuer

holy crap this is actually happening? i thought we’d be paying $500 a month for Eliquis forever. glad the gov finally got guts. my grandpa’s gonna thank you guys in his sleep.

Siobhan Goggin

This is one of the most significant healthcare reforms in a generation. The fact that savings are being passed directly to patients without requiring any action on their part is both elegant and necessary. Long overdue.

Vikram Sujay

The philosophical underpinning of this policy is profound: healthcare is not a commodity to be maximized for profit, but a social good to be equitably distributed. The notion that a life-saving drug should be priced according to market speculation rather than medical necessity has long been a moral failure of the American system. This marks a quiet revolution.

Jay Tejada

so the pharma bros are crying because they can’t charge $600 for a pill that costs $2 to make? shocking. also, jardiance at $130? i’d take that over the $600 version any day. even my dog could do the math.

Shanna Sung

this is all a setup for the government to take over your meds and replace them with cheap generics you dont even know what’s in them theyre already putting fluoride in the water and now this next theyll force you to take insulin made in a basement

Allen Ye

Let’s contextualize this within the broader arc of American capitalism. For decades, we allowed a private industry to monetize biological necessity - pain, chronic illness, mortality - as if it were a luxury good. The fact that we’ve reached a point where the federal government can step in and say, ‘No, this is not acceptable,’ isn’t just policy - it’s cultural recalibration. We are, at long last, beginning to treat health as a right, not a privilege auctioned to the highest bidder. The resistance we’re seeing now? That’s the sound of an outdated system screaming as it collapses under its own moral bankruptcy.

mark etang

This represents a monumental advancement in public health policy. The strategic implementation of price negotiation mechanisms demonstrates both fiscal responsibility and ethical governance. We commend the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services for their rigorous, data-driven approach.

Clint Moser

they’re using the weighted avg of private insurer rebates? that’s a backdoor subsidy. you think the pharma companies didn’t inflate private prices to set a higher baseline? this is just a shell game. and wait till you see the ‘spillover effect’ on your private plan - it’s gonna be a surprise bill disguised as savings.

jigisha Patel

The data presented is statistically significant, yet the absence of longitudinal analysis regarding R&D investment trajectories is concerning. The OMB’s dismissal of PhRMA’s projections lacks methodological rigor. One cannot assume innovation is unaffected by reduced revenue streams without controlling for alternative funding mechanisms such as public grants or international partnerships.

Jason Stafford

they’re coming for your insulin next. you think this stops at 10 drugs? watch. they’ll add 50 next year. then they’ll make you sign a form to get your meds. then they’ll decide which ones you’re ‘allowed’ to need. this is the first step to rationing. they’ve been planning this for decades.

Mandy Kowitz

so let me get this straight - after 20 years of letting drug companies rip us off, now the government steps in and suddenly we’re supposed to clap? congrats, you fixed a problem that was obvious since 2003. took you long enough. i’m sure the pharma lobbyists are sobbing into their yachts right now.

Justin Lowans

This is a triumph of collective will over corporate capture. The quiet, persistent advocacy of patients, clinicians, and researchers finally cracked open a door that had been welded shut. The ripple effects across the healthcare ecosystem - from private insurers to community clinics - are not incidental. They are the natural consequence of aligning price with value, not profit.

Uzoamaka Nwankpa

i just hope this doesn’t mean my meds will disappear... i’ve been on Xarelto for 5 years now. what if they switch me to something else? i don’t trust them. they always change things when you finally get used to them.

Chris Cantey

the real question isn’t whether prices dropped - it’s whether the pharmaceutical-industrial complex will quietly fund a new wave of ‘me-too’ drugs that are just slightly different, just expensive enough, just barely eligible for negotiation. this is a band-aid on a hemorrhage. they’ll find a way to keep the money flowing. they always do.

Abhishek Mondal

While the empirical outcomes appear favorable, one must interrogate the epistemological foundations of the ‘Maximum Fair Price’ metric - particularly its reliance on non-Medicare buyer averages, which are themselves distorted by opaque rebate structures, PBMs, and tiered formularies. Furthermore, the exclusion of biosimilars from the 11-year threshold is not merely arbitrary - it is a capitulation to biotech monopolies. One wonders whether this policy was designed to be effective, or merely politically palatable.