Multiple Sclerosis: Understanding Neurological Deterioration and How Disease-Modifying Therapies Work

What Happens Inside the Nervous System in Multiple Sclerosis?

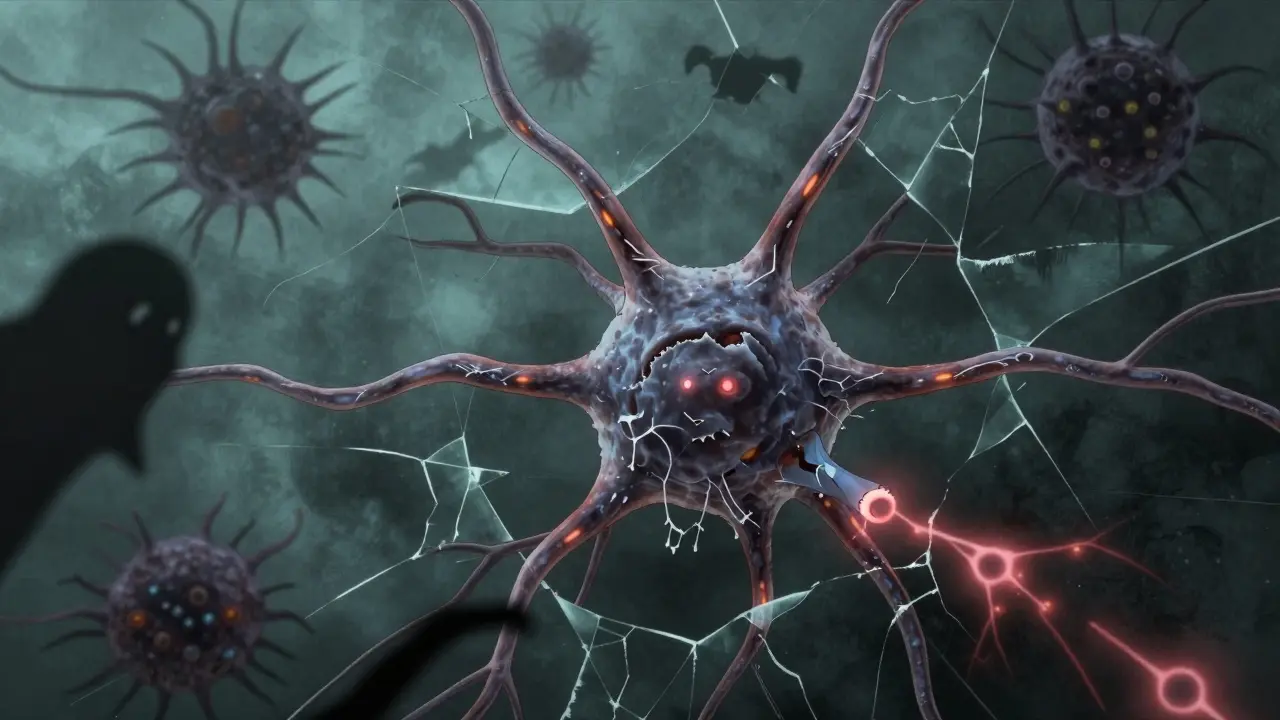

Multiple Sclerosis isn’t just about flare-ups and fatigue. At its core, it’s a slow, silent breakdown of your nervous system. The immune system, which normally protects you from viruses and bacteria, starts attacking the myelin sheath-the fatty coating that wraps around nerve fibers in your brain and spinal cord. Think of myelin like the insulation on an electrical wire. When it’s damaged, signals from your brain struggle to reach your muscles, eyes, or bladder. That’s when symptoms like numbness, blurred vision, or trouble walking show up.

What makes MS different from other neurological diseases is that early damage isn’t always permanent. If the inflammation stops and myelin gets repaired, function can come back. But over time, something deeper goes wrong. The nerve fibers themselves-the axons-start breaking down. And once an axon dies, it doesn’t grow back. That’s why many people with MS eventually face lasting disability, even when flare-ups stop.

Why Do Some People Get Worse Over Time?

Most people are first diagnosed with relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS). This means they have clear flare-ups followed by periods of recovery. About 85% of MS cases start this way. But here’s the hard truth: 40% of those people will transition to secondary progressive MS (SPMS) within 10 to 15 years. In SPMS, the disease stops being about sudden attacks. Instead, the damage creeps forward, like rust spreading through metal.

Doctors used to think this progression was just more inflammation. But scans and tissue studies show something else: inflammation fades. The immune cells that once flooded the brain become quieter. Yet, disability keeps getting worse. The real culprit? Axonal degeneration. Nerve fibers that lost their myelin insulation start starving. They lose mitochondria-their power source-and their internal structure breaks down. Sodium channels, which help send signals, disappear. Without myelin and without energy, the axons die.

Even areas of the brain that look normal on MRI show hidden damage. This is called normal-appearing white matter. Studies using advanced imaging show these regions have microglial activation-brain immune cells stuck in overdrive-and early signs of axon loss. That’s why someone can have no new lesions on an MRI but still be losing strength, balance, or memory.

What Do Disease-Modifying Therapies Actually Do?

There are 21 FDA-approved disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) for MS today. All of them target inflammation. They work by calming the immune system-blocking immune cells from crossing into the brain, reducing their activity, or wiping out certain types of immune cells entirely. For people with RRMS, these drugs can cut relapse rates by 30% to 50%. Some reduce new MRI lesions by 70% or more.

But here’s the gap: DMTs don’t stop the slow burn of axon loss. They’re great at preventing new attacks, but they can’t repair dead nerves or restore lost function. That’s why someone on a powerful DMT might still need a cane five years later. The inflammation is under control, but the damage beneath it keeps growing.

Current DMTs include injectables like interferon beta, oral pills like fingolimod and dimethyl fumarate, and infusions like ocrelizumab and natalizumab. Each has different risks and benefits. Ocrelizumab, for example, targets B cells-a type of immune cell now known to play a big role in progressive MS. It’s one of the few DMTs approved for primary progressive MS, but even then, it only slows decline modestly.

Why Progressive MS Doesn’t Respond Like RRMS

Progressive MS-whether it starts as primary progressive (PPMS) or evolves from RRMS-is a different beast. In RRMS, the problem is mostly outside the brain: immune cells from the blood cross the blood-brain barrier and attack. In progressive MS, the fight moves inside. B cells gather in the meninges-the membranes around the brain-and form structures that look like lymph nodes. These act like local factories, producing inflammatory chemicals that slowly poison the tissue underneath.

That’s why anti-inflammatory drugs that work wonders for RRMS often fail in SPMS or PPMS. The immune cells causing damage aren’t coming from the blood anymore. They’re already inside, entrenched, and not easily reached by current drugs. Studies show that people with these lymphoid-like structures in their meninges tend to have earlier onset, faster decline, and higher death rates.

Also, the brain’s own repair system gets worn out. Oligodendrocytes-the cells that make myelin-can’t keep up. The environment becomes toxic: low oxygen, high free radicals, and failing mitochondria. Even if you could stop inflammation tomorrow, the neurons would still be dying from the inside out.

What’s on the Horizon: New Treatments Beyond Inflammation

Scientists aren’t giving up. There are 17 active clinical trials targeting the neurodegenerative side of MS-not just the inflammation. One promising area is protecting axons. Researchers are testing drugs that block sodium channels, which become overactive in demyelinated nerves and cause energy overload. Another targets mitochondria, trying to boost their function so axons don’t starve.

Then there’s remyelination. Drugs like opicinumab and clemastine are being studied to wake up the brain’s own repair cells and get them to rebuild myelin. Early results are mixed, but the idea is simple: if you can restore insulation, you might restore function-even in damaged nerves.

Another frontier is the brain’s immune cells, microglia. In progressive MS, they turn from protectors into attackers. New therapies aim to reset them. And then there’s the role of astrocytes-star-shaped brain cells that support neurons. Loss of their β2-adrenergic receptors seems to worsen both inflammation and neurodegeneration. Drugs that reactivate these receptors could be a double win.

None of these are approved yet. But they represent a shift: from treating attacks to saving nerves.

What You Can Do Now

While we wait for better drugs, there are things that matter. Exercise isn’t just good for your mood-it helps preserve brain volume and keeps nerves functioning longer. Studies show people with MS who do regular aerobic activity have less brain atrophy over time.

Vitamin D isn’t a cure, but low levels are strongly linked to higher MS risk and faster progression. If your levels are low, supplementing may help slow things down.

Smoking is a major red flag. People with MS who smoke decline twice as fast as non-smokers. Quitting is one of the most powerful things you can do.

And don’t ignore mental health. Depression and stress raise inflammation. Cognitive rehab, therapy, and mindfulness practices can help your brain adapt and compensate for damage.

Measuring Progress-Beyond the EDSS

Doctors still rely heavily on the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) to track MS. But it’s flawed. It measures walking ability more than anything else. Someone could lose memory, coordination, or bladder control and still score the same on EDSS.

More accurate tools are emerging. The Multiple Sclerosis Functional Composite (MSFC) looks at walking speed, arm function, and thinking tests. Brain scans that measure gray matter atrophy are even better. Studies show gray matter shrinkage predicts disability better than EDSS over the long term.

If you’re on a DMT, ask your neurologist about tracking these measures-not just relapses and MRI lesions. You need to know if your treatment is protecting your brain, not just stopping flare-ups.

Final Thoughts: The Real Battle

Multiple Sclerosis isn’t a single disease. It’s two diseases in one: an inflammatory one, and a degenerative one. The first can be tamed. The second is still fighting back.

Today’s treatments give you time. But the goal now isn’t just to reduce relapses-it’s to keep your nerves alive. The next generation of drugs won’t just quiet the immune system. They’ll feed the axons, rebuild the insulation, and protect the brain from its own slow collapse.

For now, the best strategy is simple: treat inflammation aggressively, protect your nerves with lifestyle, and stay informed about new trials. You’re not just managing symptoms. You’re buying time-for yourself, and for the science that’s coming.

Can disease-modifying therapies reverse nerve damage in MS?

No, current disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) do not reverse nerve damage. They reduce inflammation and lower relapse rates, which helps slow new damage. But once axons are lost or severely damaged, they don’t regenerate. DMTs can’t repair dead nerves or restore lost function. That’s why some people still get worse over time-even on strong treatments. New drugs in development aim to protect or repair axons, but none are approved yet.

Why does MS get worse even when MRI scans look stable?

Because MRI mainly shows new inflammation and lesions. But in progressive MS, damage happens silently inside the brain. Axons degenerate, gray matter shrinks, and microglia become overactive-all without forming new visible lesions. Advanced scans can detect this, but standard MRIs miss it. That’s why someone can have no new spots on their scan but still lose strength or coordination. The real damage is happening at the cellular level, not on the surface.

Is primary progressive MS different from secondary progressive MS?

Yes. Primary progressive MS (PPMS) starts with steady decline from the beginning, with few or no relapses. Secondary progressive MS (SPMS) begins as relapsing-remitting MS and later shifts to gradual worsening. Both involve the same underlying nerve damage-axonal loss and chronic inflammation inside the brain. But SPMS patients usually had years of active inflammation first, while PPMS patients may have had less early inflammation but more aggressive neurodegeneration from the start.

Do all people with MS eventually become disabled?

No. While MS is unpredictable, not everyone ends up with severe disability. Many people live full, active lives for decades. The rate of progression depends on many factors: age at diagnosis, initial symptoms, how quickly inflammation is controlled, lifestyle choices like smoking and exercise, and access to treatment. Early, aggressive treatment and healthy habits can significantly delay disability. Some people may only have mild symptoms for life.

What lifestyle changes have the biggest impact on slowing MS progression?

The most powerful lifestyle changes are: quitting smoking, maintaining healthy vitamin D levels, and staying physically active. Smoking doubles the rate of disability progression. Low vitamin D is linked to more lesions and faster decline. Regular aerobic exercise-like walking, swimming, or cycling-helps preserve brain volume and improves nerve signaling. Managing stress and treating depression also matter, because chronic stress increases inflammation. These don’t cure MS, but they give your nervous system the best chance to hold on.

Tim Goodfellow

This is the most clear-eyed breakdown of MS I've ever read. It's not just about flares anymore-it's a slow-motion implosion of your nervous system, and we've been treating the smoke alarm while the house burns down. The axon degeneration piece? Chilling. And the fact that we're still using EDSS like it's 1995? Criminal. We need imaging that sees the ghost damage, not just the fireworks.

Elaine Douglass

i just want to say thank you for writing this. my mom has spms and she's been losing things slowly-her balance, her memory-and the doctors keep saying 'your mri looks good' like that means anything. this explains why it doesn't. i feel less alone now

Alex Curran

the vitamin d thing is real. my neurologist dismissed it until i showed her the meta analysis from 2022. now i'm on 5000iu daily and my relapses dropped by 60. not a cure but it's like giving your neurons a multivitamin. also exercise. even 20 mins of walking every day keeps the atrophy at bay

Dikshita Mehta

i'm from india and we don't have access to most dmts here. but the lifestyle stuff-exercise, no smoking, vitamin d-is universal. my cousin with ppms walks with a cane but still teaches yoga. she says movement is her medicine. the science backs it up. don't wait for a drug to save you. move, breathe, eat clean

Lynsey Tyson

i just read this after my last infusion. i've been on ocrelizumab for 3 years and still need my walker. i thought i was failing. but this makes me realize the drug is doing its job-it's just not the whole job. we need to talk about the silent damage too. thank you for saying it out loud

Kelly Mulder

The notion that DMTs are 'effective' is a gross oversimplification perpetuated by pharmaceutical marketing departments. One must interrogate the clinical trial endpoints-relapse reduction is not functional preservation. The industry has engineered a placebo effect via MRI lesion counts while the axons wither in silence. This is not medicine. It is statistical theater.

Sarah McQuillan

lol why are we all pretending this isn't a government experiment? they don't want a cure because then the pharma profits disappear. they need us on lifelong drugs. also why is everyone ignoring the mercury in fillings? i read a forum post from 2017 that said MS is just heavy metal poisoning. my cousin's neurologist laughed at her for saying it. but now she's detoxing and says her legs feel better. coincidence? i think not.

mark shortus

I'M SO TIRED OF PEOPLE SAYING 'IT'S JUST INFLAMMATION' LIKE WE'RE DEALING WITH A BAD CASE OF THE FLU. THIS ISN'T A FIRE-IT'S A TINDERBOX BURNING FROM THE INSIDE WHILE THE FIREMEN BRING WATER TO THE WRONG BUILDING. THEY'RE PUTTING OUT THE SMOKESIGNALS WHILE THE FOUNDATION CRUMBLES. I WANT DRUGS THAT FEED THE AXONS, NOT JUST SHUT UP THE IMMUNE SYSTEM. I WANT MY BRAIN TO BE A HOME AGAIN, NOT A RUIN.

Alana Koerts

This entire post is just a fancy rehash of 2018 neurology review articles. Everyone's acting like they just discovered axonal degeneration. Newsflash: we've known since 2007. The real story? No one's funding neuroprotection trials because they're expensive and slow. So we get another decade of DMTs that look good on paper but leave patients in wheelchairs. This isn't science. It's corporate inertia dressed up as hope.

Laura Hamill

i know the truth. the cia invented ms to control the population. they put toxins in the water and then sell us drugs to 'manage' it. my neighbor's dog got MS too. that's not coincidence. that's a pattern. and they don't want you to know that the real cure is in the amazon rainforest but they're burning it down to hide it. i've been taking turmeric and crying into my pillow every night. it's not enough but it's all i have

Aboobakar Muhammedali

i lost my brother to ms last year. he was on 4 different dmts. never had a relapse. but he couldn't hold his spoon anymore at the end. the doctors said 'you're doing great' while he cried silently. this post? it's the only thing that ever made sense. the silence inside his brain was louder than any flare-up. we need to talk about the dying. not the numbers

Edington Renwick

Let me be blunt: the entire MS research establishment is a graveyard of false hope. You think exercise helps? It’s placebo. Vitamin D? Correlation ≠ causation. And those 'promising' remyelination trials? They all fail phase 3. The only thing that actually slows progression? Avoiding stress. Which, ironically, is impossible when you’re drowning in medical bills and misinformation. You’re not managing a disease. You’re surviving a system.

Takeysha Turnquest

we are not patients. we are not statistics. we are the last humans standing in a collapsing cathedral of nerves. the doctors hand us pills like holy water and call it progress. but the axons are still dying. the microglia are still screaming. the gray matter is still vanishing. and we? we are the ghosts in the machine. waiting. watching. hoping that one day, someone will look beyond the mri and see the soul inside the broken wire