When Do Drug Patents Expire? Understanding the 20-Year Term and Real-World Timelines

Most people assume that once a drug hits the market, the company has 20 years of exclusive sales. That’s not true. The drug patent expiration date you see on paper is rarely when generics actually show up. In reality, most brand-name drugs lose market exclusivity in just 7 to 12 years - not 20. Why? Because the clock starts ticking the day the patent application is filed, not when the drug is approved. And by the time a drug gets through clinical trials, the FDA review, and manufacturing setup, half the patent term is already gone.

How the 20-Year Patent Clock Actually Works

The U.S. patent system gives pharmaceutical companies 20 years of protection from the date they file the patent application. That’s set by federal law (35 U.S.C. § 154). But here’s the catch: drug development takes years. On average, it takes 8 to 10 years just to get a new drug from lab to pharmacy shelf. That means if a company files a patent when the drug is still in early testing, they’ve already burned through half their protection before the drug even makes money. For example, if a company files a patent in 2015 and the drug gets FDA approval in 2024, the patent technically expires in 2035 - but the company only had 11 years of actual market exclusivity. That’s why the real clock isn’t 20 years. It’s whatever’s left after R&D and regulatory review.What Extends the Clock: Patent Term Adjustment and Extension

To balance this, the U.S. system has two tools: Patent Term Adjustment (PTA) and Patent Term Extension (PTE). PTA makes up for delays caused by the USPTO. If the patent office takes longer than 14 months to issue the first review, or more than three years to grant the patent, the company gets extra time added to the patent term. But if the applicant causes delays - like taking too long to respond to office actions - those days don’t count. PTE is bigger. Under the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984, companies can get up to five extra years of protection to make up for time lost during FDA review. But there’s a hard cap: the total market exclusivity - patent time plus extension - can’t go beyond 14 years after FDA approval. And if you miss the 60-day window to apply for PTE after approval, you lose it forever. Many companies miss this deadline because the paperwork is complex and the timeline is tight.It’s Not Just One Patent - It’s a Portfolio

Pharmaceutical companies don’t rely on one patent. They build a wall of them. A single drug like Humira might have 137 patents covering everything: the active ingredient, how it’s made, how it’s delivered, even how it’s used to treat different conditions. These are called secondary patents. They all have their own 20-year terms, starting from their individual filing dates. This is why some drugs stay protected long after the original patent expires. Spinraza, for example, has patent protection stretching into 2030 - not because the main compound patent lasts that long, but because of layered filings on delivery methods, formulations, and dosing schedules. This strategy, sometimes called “evergreening,” keeps generics out longer. The FTC has flagged this as a tactic that can delay generic entry by two to three years on average.

Regulatory Exclusivity: The Other Layer of Protection

Even if a patent expires, another barrier might still block generics. The FDA gives different types of exclusivity that run parallel to patents:- New Chemical Entity (NCE) exclusivity: 5 years - no generic can even apply during this time.

- Orphan Drug exclusivity: 7 years for drugs treating rare diseases (under 200,000 U.S. patients).

- New Clinical Investigation exclusivity: 3 years if the company did new studies for a new use or dosage.

- Pediatric exclusivity: 6 months added to any existing patent or exclusivity period if the company does pediatric studies requested by the FDA.

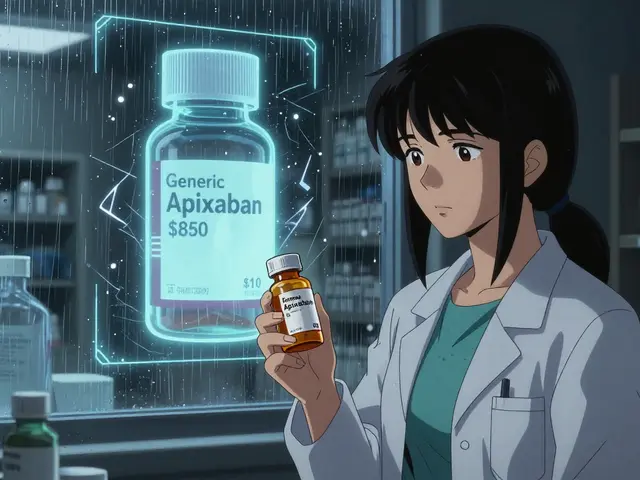

The Patent Cliff: What Happens When Exclusivity Ends

When exclusivity ends, prices drop fast. For small-molecule drugs, generic versions typically capture 90% of the market within 18 months. After Eliquis (apixaban) lost patent protection in late 2022, its price fell 62% in the first year, and generics grabbed 35% of sales in just six months. But it’s not always smooth. The first generic company to challenge a patent gets 180 days of exclusivity - meaning no other generics can enter during that time. That creates a race. Companies spend millions on lawsuits to delay that first filer. The average patent lawsuit takes over three years to resolve, and if the innovator sues within 45 days of a generic’s filing, the FDA is legally required to delay approval for 30 months. The result? A “patent cliff” - a sudden drop in revenue for the brand-name company. Evaluate Pharma predicts the industry will lose $62 billion in 2025 alone from expiring patents. For companies like AbbVie, which lost Humira’s exclusivity in 2023 after 137 patents, the revenue hit was massive.

How Companies Prepare - And How Patients Are Affected

Big pharma doesn’t wait until the last minute. They start planning patent strategy during Phase II clinical trials - roughly 7 to 8 years before approval. Teams of 15 to 25 lawyers and regulatory experts work on global patent filings across 100+ countries. The average large company holds over 8,500 active patents worldwide. Patients feel the impact too. Some insurance plans cover brand-name drugs at $50 copays while under patent. But when a pediatric exclusivity extension kicks in after patent expiry, the generic might still be priced high - and insurers might switch to a more expensive generic version. One patient reported their copay jumped from $50 to $200 during that gap - not because the drug cost more, but because the insurance didn’t yet recognize the generic as equivalent.What’s Changing in 2025 and Beyond

In early 2024, Congress proposed the “Restoring the America Invents Act,” which could cut patent term adjustments by 6 to 9 months. The USPTO is also rolling out automated systems to speed up PTA calculations - starting in late 2024. Meanwhile, the WHO is pushing for global patent terms to be reduced from 20 to 15 years to improve access to medicines. But the industry pushes back. PhRMA says the average cost to develop a new drug is $2.3 billion. Without strong patent protection, they argue, innovation would stall. The reality? The system is a balancing act. Too little protection, and companies won’t invest. Too much, and patients pay more for longer.Where to Find the Real Expiration Date

The FDA’s Orange Book is the official source for U.S. patent and exclusivity information. Every brand-name drug listed there includes the patent numbers, expiration dates, and exclusivity periods. But here’s the trick: the Orange Book doesn’t always show the full picture. Some patents are listed late, others are challenged in court, and exclusivity periods can be extended without public notice. For accurate tracking, companies like DrugPatentWatch and LexisNexis provide subscription tools that combine patent filings, litigation status, and FDA exclusivity data. For most people, though, the best bet is to check the Orange Book - or ask your pharmacist. They often know when a drug’s exclusivity ends because they see the switch to generics firsthand.How long do drug patents last in the U.S.?

Drug patents in the U.S. last 20 years from the date the patent application is filed. But because drug development takes 8-10 years, most drugs only have 7-12 years of actual market exclusivity before generics can enter. Extensions can add up to 5 more years, but total exclusivity can’t exceed 14 years after FDA approval.

Can a drug still be protected after its patent expires?

Yes. Even after a patent expires, the FDA may still block generics due to regulatory exclusivity. This includes 5 years for new chemical entities, 7 years for orphan drugs, 3 years for new clinical studies, and an extra 6 months for pediatric studies. These protections run separately from patents and can delay generic entry by months or years.

Why do some drugs have multiple patent expiration dates?

Pharmaceutical companies file multiple patents on the same drug - for the active ingredient, formulation, delivery method, manufacturing process, or new uses. Each patent has its own 20-year term from its filing date. This creates a “patent thicket,” where generics can’t enter until all key patents expire. For example, a drug might have its main patent expire in 2025, but a formulation patent still protects it until 2030.

Do generic drugs become cheaper immediately after patent expiration?

Yes - but not always right away. The first generic company to challenge a patent gets 180 days of exclusivity, during which no other generics can enter. After that, prices usually drop sharply. For small-molecule drugs, 90% market share for generics is common within 18 months. Prices often fall 60-80% in the first year. Biologics take longer because biosimilars are harder to develop and approve.

How can I find out when my drug’s patent expires?

Check the FDA’s Orange Book at fda.gov/orangebook. Search by brand name to see listed patents and exclusivity periods. You can also ask your pharmacist - they track this for insurance and substitution purposes. For more detailed timelines, services like DrugPatentWatch offer paid tools that combine patent, litigation, and regulatory data.

Lance Long

So let me get this straight - we’re paying $500 a pill for a drug that’s been sitting on a shelf for 12 years, while some lawyer in a suit files 137 patents on how to hold the bottle? 🤯

It’s not innovation. It’s legal jiu-jitsu.

And the worst part? We’re the ones getting thrown through the table.

Timothy Davis

You’re all missing the point. The 20-year patent clock starts at filing, yes - but PTA and PTE are not loopholes, they’re statutory remedies under 35 U.S.C. § 154 and 35 U.S.C. § 156. The FDA’s Orange Book is the only authoritative source, and even then, it’s incomplete because litigation stays aren’t reflected until after the fact. You’re conflating regulatory exclusivity with patent term - two entirely different legal regimes. If you don’t understand the Hatch-Waxman Act’s structure, you shouldn’t be commenting.

John Rose

This is actually kind of beautiful when you think about it - science, law, and capitalism all tangled up in one system designed to reward risk but punish delay.

Imagine being a scientist who spends 10 years developing a cure, only to have the clock ticking since day one. The system isn’t perfect, but without those extensions, we’d have zero new drugs.

Maybe we need better incentives, not just shorter patents.

Lexi Karuzis

EVERYTHING IS A SCAM. The FDA? In bed with Big Pharma. The USPTO? A rubber stamp for billion-dollar corporations. They’re not protecting innovation - they’re protecting profits.

Did you know that some patents are filed on *colors* of pills? Or that companies pay lawyers to refile patents on the *same molecule* just to reset the clock? It’s not legal - it’s corporate terrorism.

And now they want to cut PTA? Ha. They’ll just file 200 more patents on breathing.

Wake up, people. Your insulin isn’t expensive because of R&D - it’s expensive because they can get away with it.

Brittany Fiddes

Oh, so America’s pharmaceutical monopoly is now being justified as ‘necessary innovation’? How quaint.

In the UK, we’ve had generic access for decades without collapsing the industry - and our NHS doesn’t pay $10,000 for a single dose of a drug that costs $2 to manufacture.

It’s not rocket science. It’s greed wrapped in legalese. And your ‘20-year patent’ is just a fancy word for price gouging with a law degree.

Colin Pierce

Just wanted to add - if you’re on a drug that’s about to go generic, call your pharmacist. They often know 6–12 months ahead of time when the switch is coming.

And if your insurance is still charging you brand prices after generics hit? File a complaint with your plan. They’re supposed to pass savings on to you - but most don’t unless you push.

Small move, big impact.

Mark Alan

137 patents on ONE drug??? 😱

That’s not a drug - that’s a legal fortress.

Meanwhile, I’m paying $300 a month for a pill that was invented in 2008. 🤬

Someone get me a t-shirt that says ‘I survived the patent cliff’

💀💊

Amber Daugs

It’s disgusting how people act like this is normal. You’re literally paying for someone else’s failed research. The company didn’t invent anything - they just waited for someone else’s science to mature, then slapped on a patent and raised prices 5000%.

And now you’re defending it? What’s next? Patenting the air you breathe?

People are dying because of this. And you’re arguing about ‘incentives’?

Wake up. This isn’t capitalism. It’s extortion with a white coat.

Ambrose Curtis

man i used to think patents were cool til i found out they’re just corporate loopholes with fancy names

they file patents on the color of the pill, the shape of the capsule, the way the bottle opens - it’s like they’re trying to patent the idea of taking medicine

and then they act shocked when people get mad

we’re not mad because we’re cheap - we’re mad because we’re being played

and yeah, i know innovation costs money - but $2.3 billion? bro, that’s like 12 years of executive bonuses and yacht parties

give us the drug. we’ll figure out the rest

Linda O'neil

This is such an important topic and I’m so glad someone broke it down like this!

So many people think generics are ‘inferior’ - but they’re the exact same drug, just cheaper.

My mom switched from Eliquis to apixaban generics last year - same results, $20/month instead of $500.

We need more awareness, not more patents.

Keep sharing stuff like this - it helps real people.

Robert Cardoso

The fundamental flaw in the entire system is the conflation of intellectual property with moral entitlement. A patent is not a right to profit - it is a limited monopoly granted by the state to incentivize disclosure. The moment the incentive structure becomes a mechanism for perpetual rent-seeking, the social contract is broken.

Furthermore, the notion that ‘without 20 years, innovation dies’ is empirically false - look at the open-source pharmaceutical initiatives in India and Brazil. They produce life-saving drugs at 1/10th the cost. The issue isn’t lack of innovation - it’s lack of equitable distribution.

Patents were never meant to be wealth extraction tools.

James Dwyer

It’s wild how something so complex can be so simple in the end: if it takes 10 years to get a drug to market, the patent clock should start at approval - not filing.

That’s it. No lawsuits. No 137 patents. Just fairness.

And yeah, companies would make less - but they’d still make enough to fund the next breakthrough.

Simple fix. Hard to implement? Yeah. But not impossible.

jonathan soba

Actually, the UK doesn’t have ‘generic access’ - it has rationing. The NHS delays approvals for generics until they’re ‘cost-effective’ - which often means patients wait years. You’re romanticizing a system that denies care based on budget lines.

At least in the U.S., you can get the drug - you just pay for it.

And if you think patents are the problem, you haven’t seen what happens when you remove them entirely. Look at Russia’s pharmaceutical collapse in the ‘90s.

matthew martin

Man, I used to work in a pharmacy back in 2018. Saw the whole Humira switch go down.

One day, it’s $5,000 a vial. Next month, it’s $400.

Old folks in the store were crying - not because they were losing access, but because they finally had hope.

That’s what this is really about - not lawyers, not patents, not even money.

It’s about whether someone gets to live another year.

So yeah, the system’s broken.

But the people? They’re still fighting for each other.

Howard Esakov

It’s fascinating how Americans romanticize ‘innovation’ while ignoring the fact that 80% of foundational drug research is federally funded - through NIH grants, university labs, taxpayer dollars.

So we’re not paying for innovation - we’re paying for a private company to slap a label on public science and charge $10,000 for it.

And you wonder why the rest of the world laughs at us?

It’s not a market failure.

It’s a moral failure.